The worldwide practice of Hinduism encompasses a wide variety of beliefs. However, a prevailing belief that is shared by most, if not all, Hindus is the importance of physical and spiritual cleanliness and well-being… a striving to attain purity and avoid pollution. This widespread aspiration lends itself to a reverence for water as well as the integration of water into most Hindu rituals, as it is believed that water has spiritually cleansing powers.

• Holy places are usually located on the banks of rivers, coasts, seashores and mountains. Sites of convergence between land and two, or even better three, rivers, carry special significance and are especially sacred.Sacred rivers are thought to be a great equalizer. For example, in the Ganges, the pure are thought to be made even more pure, and the impure have their pollution removed if only temporarily. In these sacred waters, the distinctions imposed by castes are alleviated, as all sins fall away.

• Every spring, the Ganges River swells with water as snow melts in the Himalayas. The water brings life as trees and flowers bloom and crops grow. This cycle of life is seen as a metaphor for Hinduism.

• Water represents the “non-manifested substratum from which all manifestations derive” [Dr. Uma Mysorekar, Hindu Temple Society of North America] and is considered by Hindus to be a purifier, life-giver, and destroyer of evil.

• Milk and water are symbols of fertility, absence of which can cause barrenness, sterility leading to death.

• Temple Tanks are an essential part of every large Hindu temple. Every village/town/city has a temple with a sizable water tank. Conventional beliefs hold that the water of a temple tank is holy and has cleansing properties. It is an unwritten rule to take a dip in the temple tank before offering prayers to the presiding deities, thereby purifying oneself. In actuality, the tanks serve as a useful reservoir to help communities tide over water scarcity. Water in India is largely dependent on the monsoons. In case the rains fail, people can look to these temple tanks to fulfill basic water needs. These days, the tanks are mostly found in a state of neglect. They are either dried up or poorly maintained, which leads to contamination. [Nikhil Mundra, http://scienceofhinduism.blogspot.com]

HISTORICAL HINDU REFERENCES TO WATER

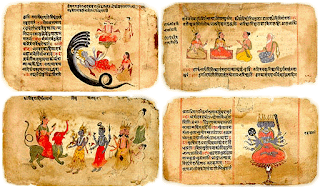

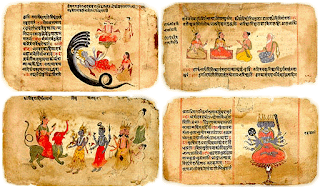

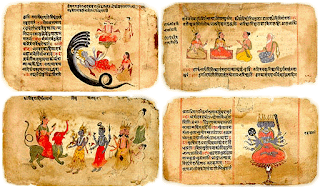

• The Matsya Avatara of Lord Vishnu is said to have appeared to King Manu (whose original name was Satyavrata, the then King of Dravida) while he washed his hands in a river. This river was supposed to have been flowing down the Malaya Hills in his land of Dravida. According to the Matsya Purana, his ship was supposed to have been perched after the deluge on the top of the Malaya Mountain. A little fish asked the king to save it and, upon his doing so, kept growing bigger and bigger. It also informed the King of a huge flood which would occur soon. The King built a huge boat, which housed his family, 9 types of

seeds, and animals to repopulate the earth after the deluge occurred and the oceans and seas receded. [Flood, Gavin (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press]

• Water image in early Indian art… Images of Ganga on a crocodile and Yamuna on a tortoise flanked the doorways of early temples. In the Varaha cave at Udayagiri, of the 4th century A.D., the two goddesses meet in a wall of water, recreating Prayaga (ancient name for Allahabad). The Pallavas at Mamallapuram, carved the story of the descent of the Ganga on an enormous rock. Later, Adi Shesha, the divine snake who forms the couch of Narayana, represented water. [Nanditha Krishna, ʻCreations Grounded in wisdom,ʼ New Indian Express, 2 May 2006]

• Etymology of the word Hindu also denotes water… Hind_ is the Persian name for the Indus River, first encountered in the Old Persian word Hindu (h_ndu), corresponding to Vedic Sanskrit Sindhu, the Indus River. The Rig Veda mentions the land of the Indo-Aryans as Sapta Sindhu (the land of the seven rivers in northwestern South Asia, one of them being the Indus). [Lipner, Julius (1998), Hindus: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, Routledge]

WATER IN HINDU RITUAL

• Water is very important for all the rituals in Hinduism. For example, water is essential as a cleaning agent, cleaning the vessels used for the poojas (rituals), and for Abhishekas or bathing of Deities. Several dravyas or nutrients used for the purpose of bathing the Deities and after use of each dravya water are used for cleansing the deity. Water offered to the Deity and the water collected after bathing the Deities are considered very sacred. This water is offered as “Theertha” or blessed offering to the devotees.

• Poorna Kumba literally means a full pitcher (“poorna” is full and “kumbha” is pitcher). The Poorna Kumbha is a pitcher full of water with fresh leaves preferably of mango tree and a coconut placed on the top. Poorna Kumbha is an object symbolizing God and it is regularly used during different religious rites. The water in the jar is said to be divine essence.

• Many of the poojas in Hinduism start with keeping a kalasa which is a brass, silver or gold pot filled with water adorned with a coconut amidst mango or other sacred leaves. Kalasa symbolizes the universe and becomes an integral part of the Mandalic-liturgy as it still forms an indispensable element of certain poojas in Hinduism. The pot is the first mandala into which the Deities descend and raise themselves.

• One of the religious rituals is tarpana, which means to please or to gratify. Specifically, tarpana is the act of pouring water through the hands with the use of sacred grass as a symbolic gesture of recognition, thanking and pleasing Gods, sages, and fathers.

• During all purification rites water is sprinkled on the objects which are to be purified. Water used to be sprinkled on any offerings to the deities.

• Before starting a meal Hindus sprinkle water around the leaf or plate in which the meal is traditionally eaten.

• In times past, a King was sprinkled with water in order to purify him during his coronation. This was believed to ensure an auspicious beginning to his reign.

• There is also an important ritual called Sandhyopasana or Sandhyavandana which is a combination of meditation and concentration. Sandhya is an obligatory duty to be performed daily for self-purification and selfimprovement. Regular Sandhya cuts the chain of old Samskaras and changes everybodyʼs old situation entirely. It brings purity, Atma-Bhava, devotion and sincerity. The important features of this ceremony are: Achamana or sipping of water with recitation of Mantras, Marjana or sprinkling of water on the body which

purifies the mind and the body, Aghamarshana or expiation for the sins of many births, and Surya Arghya or ablutions of water to the Sun-god (the other two non water-based elements of the ceremony are: Pranayama, or control of breath which steadies the wandering mind, and silent recitation of Gayatri; and Upasthana, or religious obeisance). The first part of Arghya consists of hymns addressed to water and its benefits. The sprinkling of water on the face and the head and the touching of the different organs (the mouth, nose, eyes, ears, chest, shoulders, head, etc.) with wetted fingers, are meant to purify those parts of the body and invoke the respective presiding deities on them. They also stimulate the nerve-centres and wake up the dormant powers of the body. The Arghya drives the demons who obstruct the path of the rising sun. Esoterically, lust, anger and greed are the demons who obstruct the intellect from rising up (the intellect is the sun).

• Achamana is the sipping of water three times, while repeating the names of the Lord. One becomes pure by doing Achamana after he answers calls of nature, after walking in the streets, just before taking food and after food, and after a bath.

• Jalanjali is a handful of water as an offering to the manes, gods, etc. A rite observed before an idol is installed is Jaladhivaasam (submersion in water) and Jalasthapanam is another rite.[15] Pouring water on the head in purificatory ceremony is Jalaabhishekam.

• A religious austerity to be observed in water is called Jalavaasam. It is also abiding in water. One who lives by drinking water alone is Jalaasi. A religious vow or practice in which a devotee lives by drinking water alone for one month is known as Jalakricchram.

• Chanting of mantras standing in water is Jalajapam. A kind of penance observed by standing under a continuous downpour of water is Jaladhaara. Neernila is chanting of hymns while standing in water.

• A bath performed in the holy water for the achievement of some desire is called Kaamyasnanam.[16] Prokshana is sprinkling water over oneʼs body to purify, when a bath is not possible. This is for internal as well as external purity.

• Immediately after childbirth, a close relative of the child pours a few drops of water on the body of the child using his right hand, which is called Nir talikkuka. It is said that the child will get the character of this person. As such, a close relative with good character does the ritual.

HEALTH AND WATER

• The Vedic declaration says that water offered to Sun in the evening converts the drops of water to stones that cause death to the demons. For humans, demons are like all sicknesses like typhoid TB, pneumonia etc. When a devotee takes water in his hands while standing in front of or facing the sun and drops water on the ground the rising direct Sunʼs rays fall from the head to feet of the devotee in a uniform flow. This way water heated by Sunʼs rays and its colors penetrates every part of the body. This is the reason why the Vedas direct the devotee to offer water when the Sun is about to set.

• To alleviate fevers, sprinkling holy or consecrated water on the sick person, chanting mantras is Udakashanti. While the water being sprinkled muttering a curse can affect a metamorphosis, the Hindu saints were able to curse or bless using this ʻsubhodakamʼ.

• Water Therapy, both external and internal, has been practised for centuries to heal the sick. Usha Kaala Chikitsa is Sanskrit for water therapy. According to this ancient system, 1.5 litres of water should be consumed each morning on an empty stomach, as well as throughout the day. Water Therapy is considered to be a material way of taking an “internal bath”.

• Water plays a significant role in death as well. Many funeral grounds used to be located near the rivers in India. After cremation, the mourners bathe in the river before returning to their homes. After the third day, the ashes are collected, and on the tenth day these are cast into the holy river.

THE GANGES RIVER

• The rhythm of life is dictated by water and Hindus hold the rivers in great reverence. India is a country that not only nurtures resources nature has bestowed upon her, but also worships them for the all-around prosperity they bring in their wake. The rivers are generally female divinities, food and life bestowing mothers. There are seven sacred rivers which are worships – Ganges, Yamuna, Godavari, Saraswati, Narmada, Sindhu, and Kaveri.

• The Ganges River is the most important of the sacred rivers. Its water used in pooja or worship if possible a sip is given to the dying. It is believed that those who bathed in Ganges and those who leave some part of themselves (hair, piece of bone, etc) on the bank will attain Swarga or the paradise of Indira.

• The river is referred to as a Goddess and is said to flow from the toe of Lord Vishnu to be spread in the world through the matted hair of Lord Siva. By holding that sacred stream touching it and bathing in its waters, one rescues oneʼs ancestors from seven generations. The merit that one earns by bathing in Ganga is such that it is incapable of being otherwise earned through the acquisition of sons or wealth for the performance of meritorious acts. The man of righteous conduct who thinks of Ganga at the time when his breath is about to leave his body succeeds in attaining to the highest end. She leads creatures very

quickly to heaven.

• According to Hindu religion a very famous king Bhagiratha did Tapasya (a self-discipline or austerity willingly expended both in restraining physical urges and in actively pursuing a higher purpose in life) for many years constantly to bring the river Ganga, then residing in the Heavens, down on the Earth to find salvation for his ancestors, who were cursed by a seer. Therefore, Ganga descended to the Earth through the lock of hair (Jata) of god Shiva to make whole earth pious, fertile and wash out the sins of humans. For Hindus in India,

the Ganga is not just a river but a mother, a goddess, a tradition, a culture and much more.

• Indian Mythology states that Ganga, daughter of Himavan, King of the Mountains, had the power to purify anything that touched her. Ganga flowed from the heavens and purified the people of India, according to myths. The ancient scriptures mention that the water of Ganges carries the blessings of Lord Vishnu’s feet; hence Mother Ganges is also known as Vishnupadi, which means “Emanating from the Lotus feet of Supreme Lord Sri Vishnu.”

• It is not uncommon to see may Hindus who bathe or wash in the sacred river Ganges chanting the following mantra or mentally repeating it: Gange ca Yamune caiva / God_vari Sarasvati / Narmade Sindhu Kaver / Jale ʻsmin sannidhim kuru / Puskar_dy_ni tirthani / Gang_dy_h saritas tath_ / _gacchantu pavitr_ni / Sn_nak_le sad_ …… Mama / Bless with thy presence / O holy rivers Ganges, Yamun_, God_vari, Sarasvati, Narmad_, Sindhu and K_veri / May Puskara, and all the holy waters and the rivers such as the Ganges, always come at the time of my bath.

• Some Hindus also believe life is incomplete without bathing in the Ganga at least once in one’s lifetime. Many Hindu families keep a vial of water from the Ganga in their house. This is done because it is prestigious to have water of the Holy Ganga in the house, and also so that if someone is dying, that person will be able to drink its water. Many Hindus believe that the water from the Ganga can cleanse a person’s soul of all past sins, and that it can also cure the ill.

• The major sacred places, located on the Ganga are Varanasi, Haridwar and Prayag and these places are treated as the holy places of India, as these are situated in the bank of the holy river.

• River Ganga holds great importance in the economic, social and cultural life of the Indian people in general, and Hindus in particular. People love to give the name of Ganga to their children. One can find millions of people in India with the name of Ganga and this signifies the love, affection and association of people

with river.

• The largest gathering of people in the world occurs at the Kumbh Mela which is a spiritual pilgrimage celebrated every three years in one of four sacred cities of India: Allahabad, Ujjain, Nasik and Haridwar. In Hindu mythology, it is said that a drop of immortal nectar was dropped at each of these locations as Gods and demons fought over the pot or kumbh that held the nectar. Millions of Hindus travel to the Mela to bathe in the Ganga, believing their sins will be washed away and they will achieve salvation. For other visitors, the festival is a fascinating spectacle of size and eccentricity.

Remember to proofreadThe relationship between culture and language is an intimate one, for language is the vehicle of human thought. Language determines a culture’s worldview. Vocabulary and syntax, with its subtle nuances and shades of meaning, determine how a culture interacts with the world. Language ultimately determines the shape of civilization.

Hinduism and Sanskrit are inseparably related. The roots of Hinduism can be traced to the dawn of Vedic civilization. From its inception, Vedic thought has been expressed through the medium of the Sanskrit language. Sanskrit, therefore, forms the basis of Hindu civilization.

As language changes, so religion changes. In the case of Hinduism, Sanskrit stood for three millennia as the carrier of Vedic thought before its dominance gradually gave way to the numerous pråk®tas or vernacular dialects that eventually evolved into the modern day languages of Hindi, Gujarati, Bengali, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, and so on. Although the foundations of Hinduism are built on the vocabulary and syntax of Sanskrit, these modern languages are now the primary carriers of Hindu thought within India. While the shift from Sanskrit to these regional languages forced a change in the meaning of words, and therefore a change in how subsequent generations interpreted the religion, the shift was at least within the context languages that were closely related to Sanskrit.

In the last century, however, a new phenomenon has been occurring. Hinduism has begun to emerge in the West in two significant forms. One is from Westerns who have come to embrace some variety of Hinduism through contact with a Hindu religious teacher. The other is through the immigration of Hindus who were born in India and who have now moved to the West. One of the first and most striking examples of the former scenario was Swami Vivekananda’s appearance in Chicago at the Parliament of World Religions in 1896. At the time, Vivekananda received wide coverage in the American press and later in Europe as he traveled to England and other parts of Europe. Along the way he created many followers. Swami Vivekananda was the trailblazer for a whole series of Hindu teachers that have come to the West and who still continue to arrive today. The incursion of so many Hindu holy men has brought a new set of Hindu vocabulary and thought to the mind of popular Western culture.

The other important transplantation of Hinduism into the West has occurred with the increase in immigration to America and other Western countries of Hindus from India. In particular, during the 1970s America saw the influx of many Indian students who have subsequently settled in America and brought their families. These groups of immigrant Hindus are now actively engaged in creating Hindu temples and other institution in the West.

As Hinduism expands in the West, the emerging forms of this ancient tradition are naturally being reflected through the medium of Western languages, most prominent of which, is English. But as we have pointed out, the meanings of words are not easily moved from one language to the next. The more distant two languages are separated by geography, latitude and climate, etc. the more the meanings of words shift and ultimately the more the worldview shifts. While this is a natural thing, it does present the danger that the emerging Hindu religious culture in the West may drift too far a field. The differences between the Indian regional language and Sanskrit are minuscule when compared to the difference between a Western language such as English and Sanskrit.

With this problem in mind, the great difficultly in understanding Hinduism in the West, whether from the perspective of conversion or from a second generation of Hindus originally born in India, is that it is all too easy to approach Hinduism with foreign concepts of religion in mind. It is natural to unknowingly approach Hinduism with Christian, Jewish and Islamic notions of God, soul, heaven, hell and sin in mind. We translate brahman as God, åtman as soul, påpa as sin, dharma as religion. But brahman is not the same as God; åtman is not equivalent to the soul, påpa is not sin and dharma is much more than mere religion. To obtain a true understanding of sacred writings, such as the Upa!ißads or the Bhagavad-gîtå, one must read them on their own terms and not from the perspective of another religious tradition. Because the Hinduism now developing in the West is being reflected through the lens of Christianity, Judaism and Islam, the theological uniqueness of Hinduism is being compromised or completely lost.

Ideally, anyone attempting to understand Hinduism should have a working knowledge of Sanskrit. Ideally, all Hindu educational institutions and temples should teach Sanskrit, and all Hindu youth should learn Sanskrit. In reality this is not occurring, nor is it likely to occur. The critical mass that it takes to create a culture of Sanskrit learning is not here.

Even within the Hindu temples that are appearing in the West as a result of Hindu immigration, the demand for Sanskrit instruction is not there. And why should it be there? After all, these first generations of Hindu immigrants themselves do not know Sanskrit. Their Hinduism is through the regional languages. One may argue that Hinduism is still related closely enough to its Sanskritic roots through the regional languages. The problem with this argument is that even these regional languages are not being aggressively taught to the new generation. And if the history of other immigrant cultures to American is any gauge, the regional languages of India will die out after one or two generations in the great melting pot of America. This means that the Hindu youth of the second generation are gradually losing their regional ethnic roots and becoming increasingly westernized.

I do not suggest that this means the end of Hinduism. In fact I see positive signs when Hindu youth come to temples for dar”ana and prayer and increasingly ask for Hindu weddings and other püjås. But it does suggest that the new Hinduism that is developing in the West will evolve in way that is divorced from its vernacular roots, what to speak of its Sanskritic roots, as Christianity in the West has developed separated from its original language base.

A solution to this problem of religious and cultural drift is to identify and create a glossary of Sanskrit religious words and then to bring them into common usage. Words such as brahman, dharma, papa should remain un-translated and become part of the common spoken language when we speak of Hindu matters. In this way, at least an essential vocabulary that contains the subtleties of Hinduism can remain in tact. To a limited extent this is already occurring. Words such as karma, yoga and dharma are a part of common English speech, although not with their full religious meanings intact. Here is a list of terms along with a summary of their meanings that I suggest should be learned and remain un-translated by students of Hinduism. These are terms taken primarily from the Bhagavad-gîtå and the ten major Upanisads.

brahman:- derived from the Sanskrit root brmh meaning to grow, to expand, to bellow, to roar. The word brahman refers to the Supreme Principle regarded as impersonal and divested of all qualities. Brahman is the essence from which all created beings are produced and into which they are absorbed. This word is neuter and not to be confused with the masculine word Brahmå, the creator god. Brahman is sometimes used to denote the syllable Om or the Vedas in general.

karma:- derived from the Sanskrit root kr meaning to do, to make. The work karma means action, work, and deed. Only secondarily does karma refer to the result of past deeds, which are more properly known as the phalam or fruit of action.

dharma:- derived from the Sanskrit root dh® meaning to hold up, to carry, to bear, to sustain. The word dharma refers to that which upholds or sustains the universe. Human society, for example, is sustained and upheld by the dharma performed by its members. In other words, parents protecting and maintaining children, children being obedient to parents, the king protecting the citizens, are acts of dharma that uphold and sustain society. In this context dharma has the meaning of duty. Dharma also employs the meaning of law, religion, virtue, and ethics. These things uphold and sustain the proper functioning of human society. In philosophy dharma refers to the defining quality of an object. For instance, liquidity is one of the essential dharmas of water; coldness is a dharma of ice. In this case we can think that the existence of an object is sustained or defined by its essential attributes, dharmas.

adharma:- the opposite of dharma. Mostly the term is used in the sense of unrighteousness, impiety or non-performance of duty.

guna:- quality, positive attributes or virtues. In the context of Bhagavad-gîtå and Såõkhya philosophy there are three gu!as of matter. Sometimes the gu!a is translated as phase or mode. Therefore the three gu!as or phases of matter are: sattva-guna, rajo-guna and tamoguna. The word gu!a also means a rope or thread and it is sometimes said that beings are “roped” or “tied” into matter by the three gu!as of material nature.

sattva:- the first of the three gunas of matter. Sometimes translated as goodness, the phase of sattva is characterized by lightness, peace, cleanliness, knowledge, etc.

rajas:- the second of the three gu!as of matter. Sometimes translated as passion, the phase of rajas is characterized by action, passion, creation, etc.

tamas:- the third of the three gu!as of matter. Sometimes translated as darkness, the phase of tamas is characterized by darkness, ignorance, slowness, destruction, heaviness, disease, etc.

îsa:- literally lord, master, or controller. ˆ”a one of the words used for God as the supreme controller. The word is also used to refer to any being or personality who is in control.

bhagavån:- literally one possessed of bhaga. Bhaga means fame, glory, strength, power, etc. The word is used as an epithet applied to God, gods, or any holy or venerable personality.

påpa:- literally påpa is what brings one down. Sometimes translated as sin or evil.

punya:- the opposite to påpa. Punya is what elevates; it is virtue or moral merit. Påpa and punya generally go together as negative and positive “credits.” One reaps the reward of these negative or positive credits in life. The more punya one cultivates the higher one rises in life, whereas påpa will cause one to find a lower position on life. Punya leads to happiness, påpa leads to suffering.

yoga:- derived from the Sanskrit root yuj, to join, to unite, to attach. The English word yoke is cognate with the Sanskrit word yoga. We can think of yoga as the joining of the åtma with the paramåtma, the soul with God. There are numerous means of joining with God: through action, karma-yoga; through knowledge, jñåna-yoga; through devotion, bhakti-yoga; through meditation, dhyåna-yoga, etc. Yoga has many other meaning. For example, in astronomy and astrology it refers to a conjunction (union) of planets.

yogî:- literally one possessed of yoga. A yogî is a practitioner of yoga.

jñåna:- derived from the Sanskrit root jñå, to know, to learn, to experience. In the context of Bhagavad-gîtå and the Upanißads, jñåna is generally used in the sense of spiritual knowledge or awareness.

vijñåna:- derived from the prefix vi added to the noun jñåna. The prefix vi added to a noun tends to diminish or invert the meaning of a word. If jñåna is spiritual knowledge, vijñåna is practical or profane knowledge. Sometimes vijñåna and jñåna are used together in the sense of knowledge and wisdom.

kåma:- wish, desire, love. Often used in the sense of sexual desire or love, but not necessarily so. Kåma is one of the four purusårthas or “goals of life,” the others being dharma, artha and moksa.

moksa:- liberation or freedom of rebirth. Moksa is one of the four purußårthas or “goals of life,” the others being dharma, artha and kåma.

artha:- wealth, not to be understood solely as material assets, but all kinds of wealth including non-tangibles such as knowledge, friendship and love. Artha is one of the four purusårthas or “goals of life” the others being dharma, kåma and moksa.

nirvåna:- blown out or extinguished as in the case of a lamp. Nirvåna is generally used to refer to a material life that has been extinguished, i.e. for one who has achieved freedom from re-birth. The term Nirvåna is commonly used in Buddhism as the final stage a practitioner strives for. The word does not mean heaven.

sånkhya:- calculating, enumeration, analysis, categorization. Modern science can be said to be a form of sånkhya because it attempts to analyze and categorize matter into its constituent elements. Sånkhya also refers to an ancient system of philosophy attributed to the sage Kapila. This philosophy is so called because it enumerates or analyses reality into a set number of basic elements, similar to modern science.

bråhmana:- a member of the traditional priestly class. The bråhma!a was the first of the four var!nas in the social system called varnåsrama-dharma. Literally the word means “in relation to brahman.” A bråhmana is one who follows the way of brahman. Traditionally a bråhmana, often written as brahmin, filled the role of priest, teacher and thinker.

ksatriya:- a member of the traditional military or warrior class. The kßatriya was the second var!a in the system of var!å”rama-dharma.

vaisya:- a member of the traditional mercantile or business community. The vaisya was the third varna in the system of varnå”rama-dharma.

südra:- a member of the traditional working class. The südra was the fourth varna in the system of varnåsrama-dharma.

varnåsrama:- the traditional social system of four var!as and four asramas. The word varna literally means, “color” and it refers to four basic natures of mankind: bråhmana, ksatriya, vaisya and südra. The asramas are the four stages of an individual’s life: brahmacarya (student), grhastha (householder), vanaprastha (retired) and sannyåsa (renounced).

satyam:- truth. The word satyam is formed from sat with the added abstract suffix. Sat refers to what is true and real. The abstract suffix yam means “ness.” Thus satyam literally means trueness or realness.

purusa:- man, male. In såõkhya philosophy purusa denotes the Supreme Male Principle in the universe. Its counterpart is prakrti.

prakrti:- material nature. In Såõkhya philosophy prakrti is comprised of eight elements: earth, water, fire, air, space, mind, intellect and ego. It is characterized by the three gunas: sattva, rajas and tamas. Prakrti is female. Purußa is male.

deva:- derived from the Sanskrit root div meaning to shine or become bright. A deva is therefore a “shining one.” The word is used to refer to God, a god or any exalted personality. The female version is devî. purusottama–comprised of two words: purusa + uttama literally meaning “highest man.” Purusottama means God. your posts before publishing.

1. What Is Hinduism?

A Christian, visiting India from the West, would surely think it strange if he or she was told by an Indian, “You are a follower of Jordanism.” Christianity, along with Judaism and Islam, hails from the region of the Jordan river. But it is unlikely that Christians, Jews and Muslims would like their faiths being lumped together under such an artificial, unscriptural category as “Jordanism.” Yet just this sort of thing was done to the followers of the indigenous religions of India. The word “Hinduism” is derived from the name of a river in present-day Pakistan, the Sindhu (also known as the Indus). Beginning around 1000 AD, invading armies from the Middle East called the place beyond the Sindhu “Hindustan” and the people who lived there the “Hindus”. (Due to the invaders’ language, the s was change to h.) In the centuries that followed, the term “Hindu” became acceptable even to the Indians themselves as a general designation for their different religious traditions. But since the word Hindu is not found in the scriptures upon which these traditions are based, it is quite inappropriate. The proper term is vedic dharma; the next two paragraphs briefly explain each of these words.

The word vedic refers to the teachings of the Vedic literatures. From these literatures we learn that this universe, along with countless others, was produced from the breath of Maha-Vishnu some 155,250,000,000,000 years ago. The Lord’s divine breath simultaneously transmitted all the knowledge humankind requires to meet the material needs and revive his dormant God consciousness of each person. This knowledge is called Veda. Caturmukha (four-faced) Brahma, the first created being within this universe, received Veda from Vishnu. Brahma, acting as an obedient servant of the Supreme Lord, populated the planetary systems with all species of life and imparted the Vedic scriptures as the guide for spiritual and material progress. Veda is thus traced to the very beginning of the cosmos.

Some of the most basic Vedic teachings seen within modern Hinduism are:

* Every living creature is an eternal soul covered by a material body.

* The souls bewildered by maya (the illusion of identifying the self with the body) must reincarnate from body to body, life after life.

* To accept a material body means to suffer the fourfold pangs of birth, old age, disease, and death.

* Depending upon the quality of work (karma) in the human form, a soul may take its next birth in a subhuman species, the human species, a superhuman species, or may be freed from birth and death altogether.

* Karma dedicated in sacrifice as directed by Vedic injunctions elevates and liberates the soul. Dharma is the essential nature of the Veda. The term dharma is translated as “duty,” “virtue,” “morality,” “righteousness,” or “religion,” but no single English word conveys the whole meaning of dharma. The Vedic sage Jaimini defined dharma as “a good the nature of a command that leads to the attainment of the highest good.” Now, there are different opinions as to what the highest good is that the Veda commands mankind to attain. These different opinions are the basis of the multifarious kinds of religious worship seen today within so-called Hinduism. From out of the gamut of Hindu piety, three great religious traditions emerge: Smarta-brahmanism, Shiva-shaktaism, and Vaishnavism. Each tradition is associated with one of the tri-murtis, the three main deities of Vedic dharma: Brahma, Shiva, and Vishnu.

The Smarta-brahmanas or hereditary priests preside over the religious affairs of millions of ordinary Hindus. These priests conduct the services for the different devatas (demigods) that bless common people with material benedictions (wealth, family happiness, good health and so on). The Smarta-brahmanas are grouped in gotras (families) that are said to descend from Caturmukha Brahma. They uphold and defend the caste system (jati-vyavastha) which determines a person’s social position in Hindu society. For a Smarta-brahmana, the main qualification of brahmanism (priesthood) is birth in a brahmana-gotra.

The Saivites and the Shaktas worship Shiva and his feminine energy Shakti, who is addressed by names like Devi, Durga, Parvati and Kali. While Brahma is the lord of cosmic creation, Shiva is the lord of cosmic devastation. Shakti is the goddess of the total material nature, or prakriti. Because Shiva is very easily pleased, those who desire rapid material advancement for little effort are especially interested in worshiping him and Shakti. The worship of Ganesha and Muruga (Kartikeya) is associated with Saivism, because they are both sons of Shiva. Also associated with Saivism and Shaktaism are left-and right-hand tantra.

Vaishnavism is the worship of Vishnu, the controller of the sattva-guna, the mode of goodness, by which everything is maintained. Brahma controls rajo-guna, the mode of passion, and Shiva controls tamo-guna, the mode of ignorance. Of these three states of material existence, goodness is topmost. The universe is created and destroyed again and again. These cycles of work by Brahma and Shiva are maintained eternally by the goodness of Vishnu. The name Vishnu means “all-pervading.” Lord Vishnu dwells in the hearts of all beings as the Supersoul, as well as within every atom. He is also the total form of the universe (visvarupa) and the origin of Brahma and Shiva. Beyond the universe, Vishnu has His own transcendental abode called Vaikuntha, the spiritual world. The original and most intimate form of Vishnu is the all-attractive, ever-youthful Sri Krishna. Lord Krishna, the eternal, omniscient, and incomparably blissful Supreme Personality of Godhead, is the speaker of the Bhagavad-gita, the most important text of the Hindu religion. The Bhagavad-gita rejects caste by birth and any form of worship motivated by material desire. Complete surrender to Krishna is said to surpass all other commands of dharma in the Vedas (see {Bhagavad-gita 18.66}). Surrender to Krishna delivers the soul from the cycle of repeated birth and death (samsaracakra) and returns the soul back home, back to Godhead.

2. What Is Vedanta?

The highest degree of Vedic education, traditionally reserved for the sannyasis (renunciants), is mastery of the texts known as the Upanisads. The Upanisads teach the philosophy of the Absolute Truth (Brahman) to those seeking liberation from birth and death. Study of the Upanisads is known as vedanta, “the conclusion of the Veda.” The word upanisad means “that which is learned by sitting close to the teacher.” The texts of the Upanisads are extremely difficult to fathom; they are to be understood only under the close guidance of a spiritual master (guru). Because the Upanisads contain many apparently contradictory statements, the great sage Vyasadeva (also known as Vedavyasa, Badarayana, or Dvaipayana) systematized the Upanisadic teachings in the Vedanta-sutra, or Brahma-sutra. Vyasa’s sutras are terse. Without a fuller explanation, their meaning is difficult to grasp. In India there are five main schools of vedanta, each established by an acarya (founder) who explained the sutras in a bhasya (commentary).

Of the five schools, one, namely Adi Shankara’s, is impersonalist. Shankara taught that Brahman has no name, form nor personal characteristics. Shankara’s school is opposed by the four Vaishnava sampradayas founded by Ramanuja, Madhva, Nimbarka, and Vishnusvami. Unlike the impersonalist school, Vaishnava vedanta admits the validity of Vedic statements that establish difference (bheda) within Brahman, as well those that establish nondifference (abheda). Taking the bheda and abheda statements together, the Vaishnava Vedantists distinguish between three features of the one Vastu Brahman (Divine Substance):

* Vishnu as the Supreme Soul (Para Brahman).

* The individual self as the subordinate soul (Jiva Brahman).

* Matter as creative nature (Mahad Brahman). The philosophies of the four Vaishnava sampradayas dispel the sense of mundane limitation ordinarily associated with the word “person.” Vishnu is accepted by all schools of Vaishnava vedanta as the transcendental, unlimited Purusottama (Supreme Person), while the individual souls and matter are His conscious and unconscious energies (cidacid-shakti).

3. What Is Siddhanta?

Each Vedantist school is known for its siddhanta, or “essential conclusion” about the relationships between God and the soul, the soul and matter, matter and matter, matter and God, and the soul and souls. Shankara’s siddhanta is advaita, “nondifference” (everything is one; therefore these five relationships are unreal). All the other siddhantas support the reality of these relationships from various points of view. Ramanuja’s siddhanta is visistadvaita, “qualified nondifference.” Madhva’s siddhanta is dvaita, “difference.” Vishnusvami’s siddhanta is suddhadvaita, “purified nondifference.” And Nimbarka’s siddhanta is dvaitaadvaita, “difference and identity.”

The Bengali branch of Madhva’s sampradaya is known as the Brahma-Madhva-Gaudiya Sampradaya, or the Chaitanya Sampradaya. In the 1700s this school presented Indian philosophers with a commentary on Vedanta-sutra written by Baladeva Vidyabhushana that argued yet another siddhanta. It is called acintya-bhedabheda-tattva, which means “simultaneous, inconceivable oneness and difference.” In recent years this siddhanta has become known to people all over the world due to the popularity of the books of His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. Acintya-bhedabheda philosophy maintains the same standpoint of “difference” as Madhva’s siddhanta on the fivefold relationship of God to soul, soul to matter, matter to matter, matter to God, and soul to soul. But acintyabhedabheda-tattva further teaches the doctrine of shaktiparinamavada (the transformation of the Lord’s shakti), in which the origin of this fivefold differentiation is traced to the Lord’s play with His shakti, or energy. Because the souls and matter emanate from the Lord, they are one in Him as His energy yet simultaneously distinct from Him and one another. The oneness and difference of this fivefold relationship is called acintya, or inconceivable, because, as Srila Prabhupada writes in his purport to Bhagavad-gita 18.78, “Nothing is different from the Supreme, but the Supreme is always different from everything.” As the transcendental origin and coordinator of His energies, God is ever the inconceivable factor.

4. Shankara and Buddhism

Sometimes Shankara’s advaita-vedanta commentary is presented in books about Hinduism as if it were the original and only vedanta philosophy. But in fact Shankara’s philosophy is more akin to Buddhism than vedanta. Buddhism is a nastika, or non-Vedic, religion. Before 600 AD, the time of Shankara’s appearance, most Vedantist scholars did not endorse a doctrine of impersonalism. Evidence gathered from the writings of pre-Shankara Buddhist scholars shows that their Vedantist contemporaries were Purusa-vadins (purusa = “person”, vadin = “philosopher”). Purusavadins taught that the goal of Vedanta philosophy is the Mahapurusa (Greatest Person). Bhavya, an Indian Buddhist author who lived centuries before Shankara, wrote in the Madhyamika-hrdaya-karika that the Vedantists of his time were adherents of the doctrine of bhedabheda (difference and nondifference). That Shankara borrowed Buddhistic ideas was noted by the Buddhists themselves. A Buddhist writer named Bhartrhari, a contemporary of Shankara, expressed some surprise that although Shankara was a brahmana scholar of the Vedas, his impersonal teachings resembled Buddhism. This is admitted by the followers of Shankara themselves. Pandit Dr. Rajmani Tigunait of the Himalayan Institute of Yoga is a present-day exponent of advaita-vedanta; in his book, Seven Systems of Indian Philosophy, he writes that the ideas of the Buddhist Sunyavada (voidist) philosophers are very close to Shankara’s. Shankara inserted into Vedantic discourse the Buddhistic idea of ultimate emptiness, substituting the Upanisadic word brahman (“the Absolute”) for sunya (“the void”). Because Shankara argued that all names, forms, qualities, activities and relationships are creations of maya (illusion), even divine names and forms, his philosophy is called mayavada (the doctrine of illusion).

However, to compare Brahman with the void is philosophically untenable. The Vedanta-sutra defines Brahman, not Maya, as the cause of everything (janmadyasya-yatah, Vedanta-sutra 1.1.2). How can that which lacks name, form, quality, and activity be the cause of that which possesses these features? Nil posse creari de nilo: “Nothing can be created out of nothing.” Mayavadi vedanta avoids the issue of causation by arguing that the world, though empirically real, is ultimately a dream. But dreams also have elaborate causes.

5. Differences Among the Four Vaishnava Sampradayas

The four Vaishnava sampradayas all agree that Vishnu is the cause, but they explain His relationship with His creation differently. In visistadvaita, the material world is said to be the body of Vishnu, the Supreme Soul. But the dvaita school does not agree that matter is connected to Vishnu as body is to soul, because Vishnu, God, is transcendental to matter. The world of matter is full of misery, but since Vedanta-sutra 1.1.12 defines God as anandamaya (abundantly blissful), how can nonblissful matter be His body? The truth, according to the dvaita school is that matter is ever separate from Vishnu but yet is eternally dependent upon Vishnu; by God’s will, says the dvaita school, matter becomes the ingredient cause of the world. The suddhadvaita school cannot agree with the dvaita school that matter is the ingredient cause, because matter has no independent origin apart from God. Matter is actually not different from God in the same way an effect is not different from its cause, although there is an appearance of difference. The example of the ocean and its waves is given by suddhadvaita philosophers to illustrate their argument that the cause (the ocean) is the same as the effect (the waves). The dvaitadvaita school agrees that God is both the cause and effect but is dissatisfied with the suddhadvaita school’s standpoint that there is really no difference between God and the world. The dvaitadvaita school says that God is neither one with nor different from the world –He is both. A snake, the dvaitadvaita school argues, can neither be said to have a coiled form nor a straight form. It has both forms. Similarly, God’s “coiled form” is His transcendental nonmaterial aspect, and His “straight form” is His mundane aspect. But this explanation is not without problems. If God’s personal nature is eternity, knowledge, and bliss, how can the material world, which is temporary, full of ignorance, and miserable, be said to be just another form of God?

6. Reconciliation of the Four Vaishnava Viewpoints

The Chaitanya school reconciles these seemingly disparate views of God’s relationship to the world by arguing that the Vedic scriptures testify to God’s acintya-shakti, “inconceivable powers.” God is simultaneously the cause of the world in every sense and yet distinct from and transcendental to the world. The example given is of a spider and its web. The web emanates from the spider’s body, so the spider may be taken as the ingredient cause of the web. But that does not make the spider and the web one and the same. The spider is always a separate and distinct entity from its web. Yet again, while the spider never is the web, the existence of the web cannot be separated from the spider.

There is a further lesson to be learned from this example: while the spider is clearly different from its web-creation, it nonetheless is acutely conscious of every corner of it. In philosophical terms, we could say the spider is transcendental to the web by its identity, yet simultaneously immanent throughout the web by its knowledge. This is a simple yet powerful demonstration of acintya-bhedabheda-tattva. Lord Krishna, in Bhagavad-gita 9.4 and 5, says He pervades the whole universe by His complete awareness of the spiritual and material energies that make up the creation. Yet at the same time, in His identity as the source of everything, He stands apart from the cosmic manifestation.

The web is compared to God’s maya-shakti (power of illusion), which emanates from the Real but is not real itself. “Not real” means that the features of maya (the tri-guna, or three modes of material nature: goodness, passion, and ignorance) are temporary. “Not real” does not mean the material world does not exist. The essential ingredient (vastu) of the world is real, because it is the energy of God. But the form this energy takes at the time of cosmic creation is temporary. Therefore the maya-shakti is said to be unreal. Reality is that which is eternal: God and God’s svarupa-shakti (spiritual energy). The temporal features of the material world are manifestations of the maya-shakti, not of God Himself. These features of maya bewilder the souls of this world, but they cannot bewilder God. God appears within this material world as the supreme person, yet He is not bound by this world, exactly as a spider moving anywhere in its web-creation is not bound by it.

7. Sanatana-dharma

Brahman, the Absolute Truth, the goal of vedanta, may be achieved in two ways. One way is by vedanta-darshan, or the philosophical comprehension of the conclusion of the Vedas, as described previously. Another way is by sanatana-dharma, the eternal religion of vedanta. Both darshan and sanatana-dharma are taught in the Bhagavad-gita, spoken by Sri Krishna to His disciple Arjuna 5000 years ago at Kuruksetra.

Darshan is explained in Bhagavad-gita 7.19:

bahunam janmanam ante jnanavan mam prapadyate vasudevah sarvam iti sa mahatma su-durlabhah

“After many births and deaths, he who is actually in knowledge surrenders unto Me, knowing Me to be the cause of all causes and all that is. Such a great soul is very rare.”

Sanatana-dharma is explained in Bhagavad-gita 18.66. This verse is the culmination of the entire text:

sarva-dharman parityajya mam ekam saranam vraja aham tvam sarva-papebhyo moksayisyami ma sucah “Abandon all varieties of religion and just surrender unto Me. I shall deliver you from all sinful reactions. Do not fear.”

In both darshan and sanatana-dharma, surrender to Krishna is the goal, because Krishna is the goal of the Vedas, as confirmed in Bhagavad-gita 15.15: vedais ca sarvair aham eva vedyo vedanta-krd veda-vid eva caham, “By all the Vedas, I am to be known. Indeed, I am the compiler of vedanta, and I am the knower of the Vedas.”

What is the difference between religion (dharma) that is eternal (sanatana) and religion that is not eternal? The noneternal religion, which in Bhagavad-gita 18.66 Krishna asks us to give up, is of two types: bhoga-dharma and tyaga-dharma.

Bhoga-dharma, the religion of work (karma) for sensual pleasure in this life and the next, is summed up in Bhagavad-gita 2.42-43 thusly:

“Men of small knowledge are very much attached to the flowery words of the Vedas, which recommend various fruitive activities for elevation to heavenly planets, resultant good birth, power, and so forth. Being desirous of sense gratification (bhoga) and opulent life (aisvarya), they say that there is nothing more than this.”

Tyaga-dharma, the religion of withdrawal from karma, is rejected by Lord Krishna in this verse:

“Not by merely abstaining from work can one achieve freedom from reaction, nor by renunciation alone can one attain perfection.” (Bhagavad-gita 3.4)

Sanatana-dharma, the eternal religion, is bhakti-yoga, the yoga of devotional service to Lord Krishna. Shunning both work for selfish pleasure and the stoppage of all work, the bhaktiyogi works only for Krishna’s pleasure. Bhakti-yoga liberates the soul from entanglement in the web of tri-guna (the three modes of material nature) and transfers the liberated soul to Krishna. Krishna’s transcendental personal form is the source and basis of the impersonal Brahman effulgence (brahmajyoti), which shines forever beyond the darkness of material nature. This is all confirmed in Bhagavad-gita 14.26 and 27:

“One who engages in full devotional service, unfailing in all circumstances, at once transcends the modes of material nature and thus comes to the level of Brahman.”

“And I am the basis of the impersonal Brahman, which is immortal, imperishable and eternal and is the constitutional position of ultimate happiness.”

Sanatana-dharma is exemplified in the lives of the mahatmas, or great souls. Their religious practices are described in Bhagavad-gita 9.14 and 15:

“O son of Prtha, those who are not deluded, the great souls, are under the protection of the divine nature. They are fully engaged in devotional service because they know Me as the Supreme Personality of Godhead, original and inexhaustible.”

“Always chanting My glories, endeavoring with great determination, bowing down before Me, these great souls perpetually worship Me with devotion.”

Krishna spoke the Bhagavad-gita shortly before the beginning of the Kali-yuga, the present age of darkness, sin, and quarrel. After Krishna departed this world, mayavada philosophy became prominent. Because mayavada philosophy denies that Krishna is the eternal, transcendental Personality of Godhead, and because it distorts His teachings on bhakti-yoga with impersonal speculation, it thwarts both the method and goal of sanatana-dharma. Modern Hindus, confused by mayavada ideas, think mundane politics and social work are the method of dharma. And they think the goal of dharma is the impersonal jyoti (light). The mayavadis claim the jyoti is the truth behind God’s personal form. But this claim is in direct opposition to Bhagavad-gita 14.27. Thus the path of the mahatmas given in the Bhagavad-gita is lost in much of Hinduism today.

Taking compassion upon the unfortunate, misguided souls of Kali-yuga, Lord Krishna descended again, only 500 years ago, to show mankind by His own example how to practice sanatana-dharma according to the Bhagavad-gita. This incarnation of Krishna is the Golden Avatara, Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. Lord Chaitanya accepted initiation from Isvara Puri of the Madhva Sampradaya. From Madhva’s school, Lord Chaitanya accepted two principles: (1) opposition to and defeat of mayavada philosophy, and (2) worship of the transcendental form of Lord Krishna as the path of eternal religion. The first principle is darshan, and the second is sanatana-dharma. These two principles are the philosophical and religious foundation of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), established by His Divine Grace

A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada.

In Bhagavad-gita 4.2, Lord Krishna declares that the principles of eternal religion are handed down via the guru-parampara (disciplic succession). The parampara system protects eternal religious principles from corruption by unauthorized teachers who, without following the principles themselves, interpret the Bhagavad-gita through their speculative opinions. The disciplic succession of Madhva and Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu is known as the Brahma Sampradaya, because it originates with Brahma, who received Vedic knowledge from Krishna at the beginning of creation. Brahma’s disciple is Narada, and Narada’s disciple is Vyasa, who composed the Vedanta-sutra. After Lord Chaitanya accepted this sampradaya as His own, it was called the Brahma-Madhva-Gaudiya Sampradaya. In our time, this disciplic succession and its teachings of sanatana-dharma are represented to the whole world by ISKCON. Following in the parampara tradition, members of ISKCON refrain from adharma (irreligion) in the form of meat-eating, illicit sex, gambling, and intoxication, and follow sanatana-dharma as shown by the mahatmas.

8. The Avataras of Godhead

After explaining that eternal religious principles are handed down via guru-parampara, Lord Krishna then told Arjuna that from time to time, the system of disciplic succession breaks down. This is called dharmasya glanih, the disruption of dharma. When dharma is disrupted, humanity’s very purpose is disrupted. The Vedic scriptures state, “Both animals and men share the activities of eating, sleeping, mating and defending. But the special capacity of the humans is that they are able to engage in spiritual life (dharma). Without spiritual life, humans are no better than animals.” (Hitopadesa) In order to save humanity from the animalism of irreligion, Lord Krishna says tadatmanam srjamy aham: “At that time I descend Myself.”

(B.g. 4.7)

When Sri Krishna descends from the world of spirit into the world of matter, His appearance here is called avatara. The Sanskrit word avatara is often rendered into English as “incarnation.” It is wrong, however, to think that Krishna incarnates in a body made of physical elements. The seventh and eighth chapters of Bhagavad-gita distinguish at length between the material nature (apara-prakrti), visible as the temporary substances of earth, water, fire, air and ethereal space, and God’s own spiritual nature (para-prakrti), which is invisible (avyakta), eternal (sanatana) and infallible (aksara). When the Lord descends, by His mercy the invisible becomes visible. As Krishna states in B.g. 4.6, “I descend by My own nature, incarnating in My form of spiritual energy” (prakrtim svam adhisthaya sambhavamy atma-mayaya). In 4.9 He declares, janma karma ca me divyam, “My appearance and activities are divine.” Only fools think Krishna takes birth as does an ordinary human being (B.g. 9.11).

God has many incarnations. But of all of them, that form described in Bhagavad-gita 11.50 as the most beautiful (saumya-vapu) is God’s own original form (svakam rupam). This is the eternal form of Krishna, the all-charming lotus-eyed youth whose body is the shape of spiritual ecstasy. The Srimad Bhagavata Purana confirms that Krishna is the original form of Vishnu: ete camsa-kalah pumsah krishnas tu bhagavan svayam indrari-vyakulam lokam mrdayanti yuge yuge, which means, “All of the incarnations of Vishnu listed in the scriptures are expansions of the Lord. Lord Sri Krishna is the original Personality of Godhead. All avataras appear in the world whenever there is a disturbance created by the atheists. The Lord incarnates to protect the theists.” (Srimad-Bhagavatam 1.3.28)

The Srimad-Bhagavatam provides us with the authorized list of scheduled incarnations of Godhead, of whom the dasavatara (ten avataras) are particularly celebrated. The ten are Matsya (the Lord’s form of a gigantic golden fish), Kurma (the turtle), Varaha (the boar), Sri Nrsingha (half-man, half-lion), Parasurama (the hermit who wields an ax), Vamana (a small brahmana boy), Sri Rama (the Lord of Ayodhya), Baladeva (Lord Krishna’s brother), Buddha (the sage who cheated the atheists), and Kalki (who will depopulate the world of all degraded, sinful men).

There are two broad categories of avataras. Some, like Sri Krishna, Sri Rama and Sri Nrsingha, are Vishnu-tattva, direct forms of God Himself, the source of all power. Others are individual souls (jiva-tattva) who are empowered by the Lord in one or more of seven ways: with knowledge, devotion, creative ability, personal service to God, rulership over the material world, power to support planets, or power to destroy rogues and miscreants. This second category of avatara is called shaktyavesa. Included herein are Buddha, Christ and Muhammed.

The Mayavadis think that “form” necessarily means “limitation.” God is omnipresent, unlimited and therefore formless, they argue. When he reveals His avatara form within this world, that form, being limited in presence to a particular place and time, cannot be the real God. It is only an indication of God. But in fact it is not God’s form that is limited. It is only the Mayavadis’ conception of form that is limited, because that conception is grossly physical. God’s form is of the nature of supreme consciousness. Being spiritual, it is called suksma, “most subtle.” There is no contradiction between the omnipresence of something subtle and its having form. The most subtle material phenomena we can perceive is sound. Sound may be formless (as noise) or it may have form (as music). Because sound is subtle, its having form does not affect its ability to pervade a huge building. Similarly, God’s having form does not affect His ability to pervade the entire universe. Since God’s form is finer than the finest material subtlety, it is completely inappropriate for Mayavadis to compare His form to gross hunks of matter.

Because they believe God’s form is grossly physical, Mayavadis often argue that any and all embodied creatures may be termed avataras. Any number of “living gods” are being proclaimed within India and other parts of the world today. Some of these gods are mystics, some are charismatics, some are politicians, and some are sexual athletes. But none of them are authorized by the Vedic scriptures. They represent only the mistaken Mayavadi idea that the one formless unlimited Truth appears in endless gross, physical human incarnations, and that you and me and I and he are therefore all together God. And since each god has a different idea of what dharma is, the final truth, according to mayavada philosophy, is that the paths of all gods lead to the same goal. This idea is as unenlightened as it is impractical.

When ordinary people proclaim themselves to be God, and that whatever they are doing is Vedic dharma, that is dharmasya glanih, a disturbance to eternal religious principles. Therefore Krishna came again, 500 years ago, as the Golden Avatara, Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. He established the yuga-dharma, the correct form of sanatana-dharma for our time. Sri Chaitanya’s appearance was predicted in Srimad-Bhagavatam 11.5.32: “In this Age of Kali, people who are endowed with sufficient intelligence will worship the Lord, who is accompanied by His associates, by congregational chanting of the holy names of God.”

The Avatara of the Deity and the Holy Name

The transcendental vibration hare krishna, hare krishna, krishna krishna, hare hare / hare rama, hare rama, rama rama, hare hare is the avatara of the Lord in the form of the holy name (kali-kale nama-rupe krishna-avatara, from Chaitanya-caritamrta Adi-lila 17.22). Anyone can prove to his own satisfaction that the Lord and His name are not different simply by chanting this spiritual sound constantly. The proof is the transcendental bliss (kevala-ananda) that envelops the soul the more the holy name is chanted. This higher taste renders insignificant the taste for degraded material pleasures like illicit sex, meat-eating, gambling and intoxication. Anarthopasamam saksad bhakti-yogam adhoksaje: the eternal religion, or the yoga of pure devotion (bhakti) to Krishna, is evinced by the disappearance of sinful habits (anarthas.)

As Krishna appears in the sound of His holy name, so also He appears within the arca-avatara, His incarnation as the Deity worshiped in the temple. The central focus of every ISKCON temple around the world is the worship of Krishna’s Deity form as represented in stone, metal, wood or as painted pictures. Through ceremonial services (puja) conducted according to Vedic tradition, the devotees fulfill the Lord’s injunction in Bhagavad-gita 9.27: “Whatever you do, whatever you eat, whatever you offer or give away, and whatever austerities you perform –do that, O son of Kunti, as an offering to Me.” This puja purifies the minds and senses of the devotees and connects them to Krishna in an attitude of love.

Mayavadis decry service to the Deity as idol worship. They argue that God is not present within the Deity, because He is everywhere. But if He is everywhere, then why is He not within the Deity as well? Moisture is also everywhere, even within the air. But when one needs a drink of water, he cannot get it from the air. He must drink the water from where water tangibly avails itself to be drunk: from a faucet, a well, or a clear stream. Similarly, although God is everywhere, it is in His Deity form that He makes Himself tangibly available for worship.

9. Liberation in Krishna Consciousness

“Back home, Back to Godhead” –what does it mean? It means the return of our consciousness to Krishna. Consciousness is the symptom of the soul and the reservoir of our desires. As conscious souls, each one of us is a tiny aspect of Krishna’s personal spiritual potency (see Bhagavad-gita 15.7). Just as Krishna is eternally a person, so are we. But now our original personal nature is covered by Maya (illusion). Maya diverts consciousness away from Krishna. The temporary forms of the material world then become the objects of our consciousness and all its desires. Thus prema (the soul’s love for God) is perverted into kama (lust for material sense gratification). As long we confuse lust for love, we must take birth in this world again and again. For a devotee of Krishna, the method of liberation from birth and death is the method of purifying consciousness and desires until the ecstasy of pure Krishna consciousness is achieved. As the word ecstasy indicates (Greek ekstasis, “outside the body”), Krishna consciousness transports the soul beyond identification with the material body.

All the great religions of mankind teach that this present life is meant to cultivate the afterlife of the soul. Among the various sects within Judaeo-Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism, two paths of cultivation can be discerned: 1) the path of elevation, and 2) the path of salvation.

1) The elevationists aim for an elevated state of material happiness in the afterlife. Their hope is to join their family and friends in the celestial realm known as heaven in the Bible and svarga in the Vedas. The Bhagavad-gita warns that although life in heaven is much longer than on earth, it is not eternal: “When they have thus enjoyed vast heavenly sense pleasure and the results of their pious activities are exhausted, they return to this mortal planet again. Thus those who seek sense enjoyment by adhering to the principles of elevation achieve only repeated birth and death.” (Bhagavad-gita 9.21)

2) Salvationists, on the other hand, aim to be saved from their mortality. Buddhists, Mayavadi Hindu Vedantists, as well as Judaeo-Christian and Islamic Sufi mystics, often speak of salvation as the surrender of the mortal self to the eternal light that is Nirvana, Brahman or God. Some speak of salvation as a state of unbroken prayerful contemplation upon a personal deity. These are descriptions of impersonal Brahman and Paramatma realization. Impersonal Brahman, as explained in previous articles, is the formless effulgence of Lord Krishna’s personal form. Mystics and yogis who are able to negate their minds’ attachments to the world of material form may lose themselves within this formless light. Paramatma is Krishna’s form as the Supersoul, who dwells within the hearts of all living beings as the overseer and permitter (see Bhagavad-gita 13.23). Paramatma realization is semi-personal, because the salvationist’s relationship to the Supersoul in the heart remains passive. More than wanting to serve God, the salvationist wants to be saved from death and rebirth. Thus impersonal Brahman and semi-personal Paramatma realization are incomplete.

A famous verse in Srimad-Bhagavatam explains how complete realization of the Personality of Godhead is to be cultivated.

sravanam kirtanam visnoh smaranam pada-sevanam arcanam vandanam dasyam sakhyam atma-nivedanam

“Hearing and chanting about the transcendental holy name, form, qualities, paraphernalia and pastimes of Lord Krishna, remembering them, serving the lotus feet of the Lord, offering the Lord respectful worship with sixteen types of paraphernalia, offering prayers to the Lord, becoming His servant, considering the Lord one’s best friend, and surrendering everything unto Him (in other words, serving Him with the body, mind and words) –these nine processes are accepted as pure devotional service.” (Srimad-Bhagavatam 7.5.23)

After the steady practice of these nine processes awakens the ecstasy of love of Krishna in the devotee’s heart, Krishna appears before the devotee. At that time all the senses of the devotee (the eyes, nose, ears, tongue, sense of touch) become the receptacles of the auspicious qualities of Krishna: His supreme beauty, fragrance, melody, youthfulness, tastefulness, munificence and mercy. The Lord reveals first His beauty to the eyes of the devotee. Due to the sweetness of that beauty, all the senses and the mind take on the quality of eyes. From this the devotee swoons. To console the devotee, the Lord next reveals His fragrance to the nostrils of the devotee, and by this, the devotee’s senses take on the quality of the nose in order to smell. Again the devotee swoons in bliss. The Lord then reveals His sonorous voice to the devotee’s ears. All the senses become like ears to hear, and for the third time the devotee faints. The Lord then mercifully gives the touch of His lotus feet, His hands and His chest to the devotee, and the devotee experiences the Lord’s fresh youthfulness. To those who love the Lord in the mood of servitude, He places His lotus feet on their heads. To those in the mood of friendship, He grasps their hands with His. To those in the mood of parental affection, with His hand He wipes away their tears. Those in the conjugal mood He embraces, touching them with His hands and chest. Then the devotee’s senses all take on the sense of touch and the devotee faints again. In this way, the devotee attains his rasa (spiritual relationship) with Krishna. There are five rasas: santa (passive awe and reverence); dasya (servitude); sakhya (friendship); vatsalya (parenthood); and madhurya (conjugal love). The most fortunate salvationists can attain only the santa-rasa. The four higher rasas are reserved for Krishna’s pure devotees.

By flooding the senses with eternal nectar from the original, pure source of pleasure –God Himself –love of Krishna completely liberates the devotee from attraction to temporary material sense pleasures. Thus the consciousness of the soul completely takes shelter of its original position as an eternal associate of the Lord in the spiritual world. As long as he or she still possesses a physical body, the fully Krishna conscious devotee is called jivan-mukta, liberated while still within the material world. When he or she gives up the physical body, the fully Krishna conscious devotee remains forever with Krishna in the spiritual world. This is videha-mukti, liberation that transcends the material world altogether. According to the kind of rasa achieved, the soul in liberation displays a spiritual form as Krishna’s eternal servant, friend, parent or conjugal lover. Just as our present material body permits us to engage in karma (physical activities), so the spiritual rasa-body permits us to engage in lila (Krishna’s endlessly expanding spiritual activities).

1. What Is Hinduism?

A Christian, visiting India from the West, would surely think it strange if he or she was told by an Indian, “You are a follower of Jordanism.” Christianity, along with Judaism and Islam, hails from the region of the Jordan river. But it is unlikely that Christians, Jews and Muslims would like their faiths being lumped together under such an artificial, unscriptural category as “Jordanism.” Yet just this sort of thing was done to the followers of the indigenous religions of India. The word “Hinduism” is derived from the name of a river in present-day Pakistan, the Sindhu (also known as the Indus). Beginning around 1000 AD, invading armies from the Middle East called the place beyond the Sindhu “Hindustan” and the people who lived there the “Hindus”. (Due to the invaders’ language, the s was change to h.) In the centuries that followed, the term “Hindu” became acceptable even to the Indians themselves as a general designation for their different religious traditions. But since the word Hindu is not found in the scriptures upon which these traditions are based, it is quite inappropriate. The proper term is vedic dharma; the next two paragraphs briefly explain each of these words.

The word vedic refers to the teachings of the Vedic literatures. From these literatures we learn that this universe, along with countless others, was produced from the breath of Maha-Vishnu some 155,250,000,000,000 years ago. The Lord’s divine breath simultaneously transmitted all the knowledge humankind requires to meet the material needs and revive his dormant God consciousness of each person. This knowledge is called Veda. Caturmukha (four-faced) Brahma, the first created being within this universe, received Veda from Vishnu. Brahma, acting as an obedient servant of the Supreme Lord, populated the planetary systems with all species of life and imparted the Vedic scriptures as the guide for spiritual and material progress. Veda is thus traced to the very beginning of the cosmos.

Some of the most basic Vedic teachings seen within modern Hinduism are:

* Every living creature is an eternal soul covered by a material body.

* The souls bewildered by maya (the illusion of identifying the self with the body) must reincarnate from body to body, life after life.

* To accept a material body means to suffer the fourfold pangs of birth, old age, disease, and death.

* Depending upon the quality of work (karma) in the human form, a soul may take its next birth in a subhuman species, the human species, a superhuman species, or may be freed from birth and death altogether.

* Karma dedicated in sacrifice as directed by Vedic injunctions elevates and liberates the soul. Dharma is the essential nature of the Veda. The term dharma is translated as “duty,” “virtue,” “morality,” “righteousness,” or “religion,” but no single English word conveys the whole meaning of dharma. The Vedic sage Jaimini defined dharma as “a good the nature of a command that leads to the attainment of the highest good.” Now, there are different opinions as to what the highest good is that the Veda commands mankind to attain. These different opinions are the basis of the multifarious kinds of religious worship seen today within so-called Hinduism. From out of the gamut of Hindu piety, three great religious traditions emerge: Smarta-brahmanism, Shiva-shaktaism, and Vaishnavism. Each tradition is associated with one of the tri-murtis, the three main deities of Vedic dharma: Brahma, Shiva, and Vishnu.

The Smarta-brahmanas or hereditary priests preside over the religious affairs of millions of ordinary Hindus. These priests conduct the services for the different devatas (demigods) that bless common people with material benedictions (wealth, family happiness, good health and so on). The Smarta-brahmanas are grouped in gotras (families) that are said to descend from Caturmukha Brahma. They uphold and defend the caste system (jati-vyavastha) which determines a person’s social position in Hindu society. For a Smarta-brahmana, the main qualification of brahmanism (priesthood) is birth in a brahmana-gotra.

The Saivites and the Shaktas worship Shiva and his feminine energy Shakti, who is addressed by names like Devi, Durga, Parvati and Kali. While Brahma is the lord of cosmic creation, Shiva is the lord of cosmic devastation. Shakti is the goddess of the total material nature, or prakriti. Because Shiva is very easily pleased, those who desire rapid material advancement for little effort are especially interested in worshiping him and Shakti. The worship of Ganesha and Muruga (Kartikeya) is associated with Saivism, because they are both sons of Shiva. Also associated with Saivism and Shaktaism are left-and right-hand tantra.

Vaishnavism is the worship of Vishnu, the controller of the sattva-guna, the mode of goodness, by which everything is maintained. Brahma controls rajo-guna, the mode of passion, and Shiva controls tamo-guna, the mode of ignorance. Of these three states of material existence, goodness is topmost. The universe is created and destroyed again and again. These cycles of work by Brahma and Shiva are maintained eternally by the goodness of Vishnu. The name Vishnu means “all-pervading.” Lord Vishnu dwells in the hearts of all beings as the Supersoul, as well as within every atom. He is also the total form of the universe (visvarupa) and the origin of Brahma and Shiva. Beyond the universe, Vishnu has His own transcendental abode called Vaikuntha, the spiritual world. The original and most intimate form of Vishnu is the all-attractive, ever-youthful Sri Krishna. Lord Krishna, the eternal, omniscient, and incomparably blissful Supreme Personality of Godhead, is the speaker of the Bhagavad-gita, the most important text of the Hindu religion. The Bhagavad-gita rejects caste by birth and any form of worship motivated by material desire. Complete surrender to Krishna is said to surpass all other commands of dharma in the Vedas (see {Bhagavad-gita 18.66}). Surrender to Krishna delivers the soul from the cycle of repeated birth and death (samsaracakra) and returns the soul back home, back to Godhead.

2. What Is Vedanta?

The highest degree of Vedic education, traditionally reserved for the sannyasis (renunciants), is mastery of the texts known as the Upanisads. The Upanisads teach the philosophy of the Absolute Truth (Brahman) to those seeking liberation from birth and death. Study of the Upanisads is known as vedanta, “the conclusion of the Veda.” The word upanisad means “that which is learned by sitting close to the teacher.” The texts of the Upanisads are extremely difficult to fathom; they are to be understood only under the close guidance of a spiritual master (guru). Because the Upanisads contain many apparently contradictory statements, the great sage Vyasadeva (also known as Vedavyasa, Badarayana, or Dvaipayana) systematized the Upanisadic teachings in the Vedanta-sutra, or Brahma-sutra. Vyasa’s sutras are terse. Without a fuller explanation, their meaning is difficult to grasp. In India there are five main schools of vedanta, each established by an acarya (founder) who explained the sutras in a bhasya (commentary).

Of the five schools, one, namely Adi Shankara’s, is impersonalist. Shankara taught that Brahman has no name, form nor personal characteristics. Shankara’s school is opposed by the four Vaishnava sampradayas founded by Ramanuja, Madhva, Nimbarka, and Vishnusvami. Unlike the impersonalist school, Vaishnava vedanta admits the validity of Vedic statements that establish difference (bheda) within Brahman, as well those that establish nondifference (abheda). Taking the bheda and abheda statements together, the Vaishnava Vedantists distinguish between three features of the one Vastu Brahman (Divine Substance):

* Vishnu as the Supreme Soul (Para Brahman).

* The individual self as the subordinate soul (Jiva Brahman).

* Matter as creative nature (Mahad Brahman). The philosophies of the four Vaishnava sampradayas dispel the sense of mundane limitation ordinarily associated with the word “person.” Vishnu is accepted by all schools of Vaishnava vedanta as the transcendental, unlimited Purusottama (Supreme Person), while the individual souls and matter are His conscious and unconscious energies (cidacid-shakti).

3. What Is Siddhanta?

Each Vedantist school is known for its siddhanta, or “essential conclusion” about the relationships between God and the soul, the soul and matter, matter and matter, matter and God, and the soul and souls. Shankara’s siddhanta is advaita, “nondifference” (everything is one; therefore these five relationships are unreal). All the other siddhantas support the reality of these relationships from various points of view. Ramanuja’s siddhanta is visistadvaita, “qualified nondifference.” Madhva’s siddhanta is dvaita, “difference.” Vishnusvami’s siddhanta is suddhadvaita, “purified nondifference.” And Nimbarka’s siddhanta is dvaitaadvaita, “difference and identity.”